Alejandro Valentin comes from a family of migrant workers. He himself has spent some time under the beating sun, working the fields.

Valentin grew up in Salinas to descendents of the Bracero program, a now-extinct migrant farm worker program that facilitated the migration of Mexican farm laborers into the United States from 1942 to 1964.

“My grandparents worked in the fields, my mom worked in the fields for a little bit, my family has a lot of history regarding immigrant farm workers,” Valentin said.

Valentin spent most of his youth speaking Spanish at home with his grandparents, who raised him. So, when he got to high school, he didn’t find Spanish to be an important class. Nonetheless, Valentin said his mom “forced” him to take it — a decision he would not regret.

“We don’t want you to lose your native tongue, it’s what defines you, it’s part of your culture,” Valentin’s grandparents reminded him.

Valentin enrolled at Cal Poly as a chemistry major with a history minor in 2020, but by his sophomore year he switched to his true passion, Spanish.

That’s where he discovered Cal Poly’s Spanish-Speaking Debate Team in Professor Marion Hart’s Spanish 302: Advanced Conversation and Composition class.

Valentin fell in love with debate despite his unfamiliarity, and a year later, he’s now the captain of the Spanish-speaking debate Team.

According to Hart, Cal Poly’s Spanish-Speaking Debate Team is the only university-funded Spanish-speaking debate program in the country. Other teams exist within urban debate leagues, and there are also student-led debate teams that raise funds independently of their institution, but none receive university funding like Cal Poly’s.

It’s one of the rare communities at Cal Poly that centers Latinx and Spanish-speaking students and the issues that they and their communities face, according to Hart and Valentin.

“One of the things my grandpa also told me was always like, if you know something’s wrong, like stand up for yourself,” Valentin said. “We’re not doing it for the competition.”

The debate topics are similarly topical and reflect the realities of those debating them, according to Hart. In their 2023-24 Legados debate series, Cal Poly’s team went up against Centro de Enseñanza Técnica y Superior (CETYS), a school in Tijuana, Mexico debating topics such as H2-A agricultural worker visas, unregistered cars in Mexico called auto-chocolates and agricultural water usage.

“You want to choose topics that are reflective of our communities,” Hart said. “A lot of our Spanish-speaking communities have agricultural experience…we don’t want to get into the kind-of isolated ivory tower of debate.”

From Mexicali to San Luis Obispo and back

One of the most rewarding parts of the Spanish-speaking debate team, according to Valentin, is the opportunity to travel to CETYS Universidad in Tijuana, Mexico, every year for a debate tournament.

CETYS and Cal Poly are a part of a one-of-a-kind debate league, Legados or “legend,” according to Hart. Each year, the teams travel to and from Mexicali and SLO to compete at their respective schools.

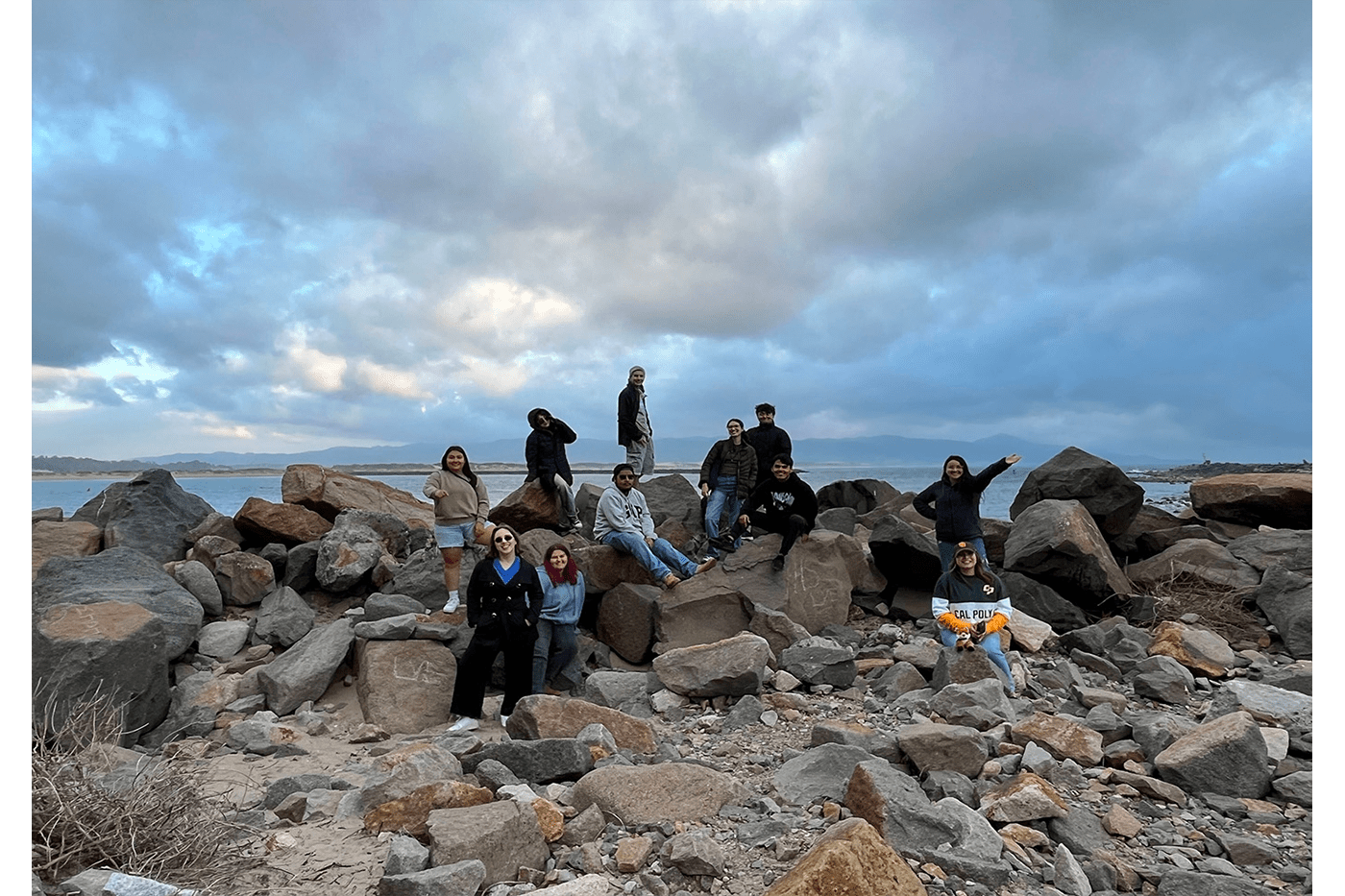

After weeks of intensive research into the debate topic of the tournament, the two teams trade the long trip. In March, the week before finals, Valentin and the rest of the Cal Poly Spanish-speaking Debate team set out on the 10-hour drive to CETYS.

“[It was] probably one of my best college experiences,” Valentin reflected on his first trip. “It was a huge bonding experience… we’re not just a team… we’re brothers and sisters.”

Sociology junior Alondra Cardoso joined the debate team her sophomore year and said the team has helped her find community.

“I’ve been through so much when it comes to public-speaking, I used to be so bad,” Cardoso reflected on her growth since joining the team. “We all get along, we all feel comfortable giving constructive criticism.”

Cardoso regarded driving down to Mexicali with her debate partners as one of her favorite experiences with the debate team.

CETYS’ team Captain Enzo Gianola found the cross-cultural dialogue between the two teams to be intellectually stimulating and fundamental to bettering society.

“We’re the next generation of people that will be in the workforce and some of us could even be in high-end positions,” Gianola said. “I would much rather have somebody who has a good notion of the world that is to an extent conscious of how the world is spinning, be in that place of power.”

Gianola added that debate helps foster dialogues between different and sometimes clashing personalities.

“I know the word ‘debate’ is very tarnished, honestly,” Gianola said. “People think of [people] screaming at each other and saying very mean things… but I hope events like these can prove that it can be a civil dialogue and it’s about constructing, not destroying each other.”

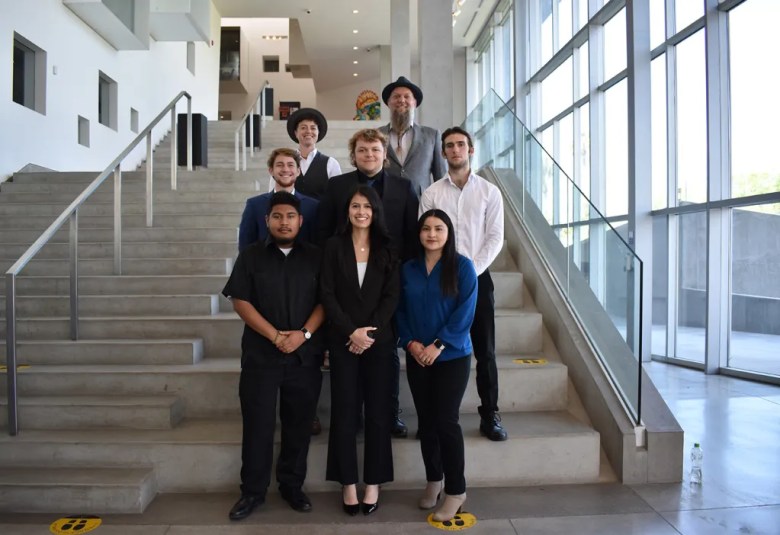

On April 13, the two teams met in room E-27 of the Math building for the final debate of the Legados debate series. The debate topic revolved around agricultural sustainability. The event was attended and judged by faculty from both universities and agriculture industry leaders.

“Like we’re not playing with chess pieces, we’re talking about people’s lives,” Gianola reflected on the debate.

Gianola’s group presented a proposal on the importance of the Colorado river which stretches all the way down into Mexicali and is an integral water source for ranchers and farmers in his locale.

Translation: California faces numerous problems in its agricultural system. We are talking about three main problems: 1. climate change, 2. the need for workers, and the third, possibly the most crucial, the lack of water.

Gianola said, on top of his courseload as a computer science major, he and his group researched their topic for 9 to 10 hours and held three practice sessions in a week. Gianola compared crafting an argument in debate to programming.

“The devil is in the details,” Gianola said.

Similarly, Valentin’s team chose something close to home in the realm of agricultural sustainability. Valentin’s family relied on the food bank growing up following his mother’s cancer diagnosis. His grandmother even volunteered at the Salinas food bank for a short period and noticed the incredible amount of food waste.

“We’re trying to promote the fact that this food that’s deemed not adequate enough for these big markets and really still has some sort of use,” Valentin said.

Valentin’s group advocated for produce capture, the process of rescuing fruits and vegetables which grocery stores would have thrown away.

Debates like these are the thesis of the Spanish-Speaking Debate program, according to Hart.

“It helps students learn how to advocate for themselves and for their communities,” Hart said.

The Spanish-Speaking Debate Team started in 2017. Seven years later the team has 10 committed members.

“What we’re doing now… is to recognize that we have a quarter of the population who speaks Spanish in the U.S.,” Hart said.

But, oftentimes a lot of those voices are left out, according to Hart.

“It’s kind of few and far between to find those communities on campus and it can be hard for people sometimes,” Hart said.

Valentin agreed. Before joining the debate team, he took everything on the cheek and had a “tough it out, who cares, it’ll be over” mentality.

“After joining the team, if I know something’s wrong… I’ll actually say something,” Valentin said.