Roger Brown had his “head cut off from the rest of his body” most of his life. He was riddled with anger and frustration, but above all – fear. He didn’t care for his own livelihood and in turn was unable to care for others.

His brother and group of friends – at the time – let him into their idea of a planned robbery. Brown didn’t know the details beforehand – nor did he bother to ask. The robbery turned deadly. The group took a witness, brought him into a field and shot him.

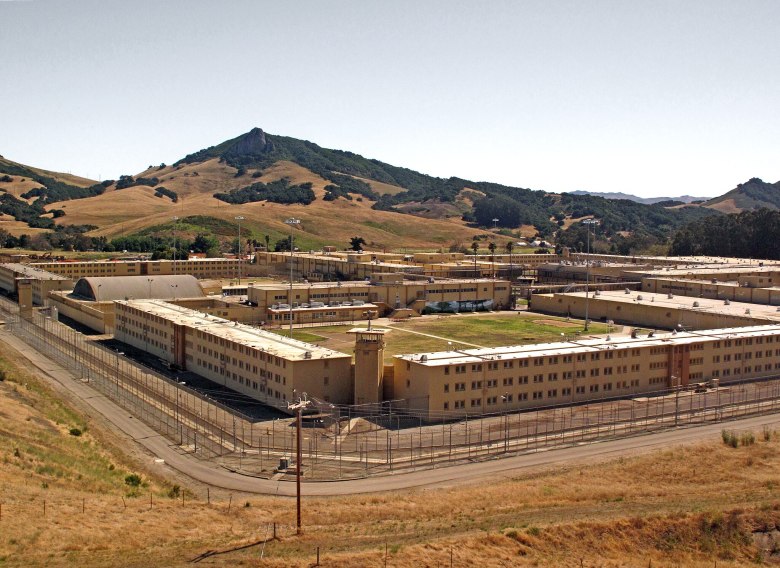

Brown began his 34 years of incarceration in 1978. He spent decades of his life in prisons like San Quentin, but spent the majority of his time at California Men’s Colony (CMC) in San Luis Obispo.

One day at CMC, he walked into a room of fellow inmates. They spent two full days together divulging their fears, passions, hopes for the future. They even played childhood games they never got to play growing up. The feeling of disconnection began to dissipate.

“AVP was one of the first things that helped me connect my head and my heart,” he said.

This was his first introduction to the Alternative to Violence Program (AVP).

AVP is a worldwide phenomenon, but has a strong network though the prison system in California. According to their website, “Through an international network of local chapters, AVP facilitators — all trained volunteers — offer workshops in prisons as well as in the community for all who would like to reduce the level of unresolved conflict in their lives and the lives of those around them.”

The fully-voluntary program helped him to reflect on his own life and connect with others through their reflections. And now, Brown helps others get through the program by volunteering in workshops along the Central Coast with his dog and companion, Leroy.

One of the places Brown conducts workshops is at CMC. The medium-level security prison sits less than three miles past Cal Poly on Highway 1, surrounded by rolling green hills. Doves and gulls build nests in the wire netting that covers the compound’s thick yellow beams.

Inmates who get approved for AVP meet for two full days, the first weekend of the month, in the compound’s gym. It looks like a middle school gym — with a basketball court and a stage — and there are three circles of 20 chairs, separated by rolling carpeted panels to block sound.

The program itinerary consists of Gatherings where the group discusses questions that connect one another to build community, Exercises build self esteem and create teamwork and Light and Livelies get people moving with subtle lessons weaved in.

One example of an Exercise is “I messages,” phrasing frustrations as “I – when this happens — feel — because this is what’s important to me.” Inmates will use these when speaking to their families over the phone as a healthy tool to communicate their feelings, according to volunteers.

There are three workshop levels — basic, advanced and training for facilitators and each one has different activities and focus points.

The workshops conclude with a graduation, with fellow inmates applauding one another.

Brown’s experience with AVP is not unique — Juvon McClenton underwent the program decades later in early May.

That weekend, McClenton was helping to facilitate AVP at CMC. A program, he said, that had given him hope.

Some inmates who attended that weekend say they’re interested in AI. Others are good at pickleball. A couple are “Swifties.” Many have been in prison for decades and are enthusiastic about the chance to heal childhood trauma and forgive themselves.

McClenton pulled back a state-issued blue sleeve to show his scars.

His body was riddled with bullet holes — 14 of them that tore through his skin before his fifteenth birthday.

“I have one here, here…” He pointed to the center of his palm. He leaned down to show a bump on the top of his smooth head left by a pistol.

He sat in the prison’s chilly gymnasium where McClenton has spent the last 30 years — serving a 196-year sentence he received when he was 17.

The stigma of incarceration had lingered over McClenton. He calls it a “corrosive tool.”

“It’s labeling, it’s divisive; it takes the sediment out of what it is to be human,” he said. “We’re not inanimate objects.”

According to McClenton, stigma causes division and “misrepresents the human condition.”

McClenton went on to say, “No one wants to cause harm.” Instead, it’s the lack of tools provided and untreated trauma that manifests into harm.

People have called him “a monster,” but fail to understand where he comes from.

McClenton was abandoned by his mother at birth. His stepmom let her four sons beat him when his dad left during the day. His father died in the county jail of kidney failure when McClenton was 12 because he needed dialysis and the sheriff refused. Before he turned 15, he was shot 14 times.

After being incarcerated, McClenton “was surprised at the fact that [he] started feeling human again.”

The program helped him with that.

“This is what this program is all about: togetherness,” he said. “No matter where we come from, we share in similar experiences. There’s more we have in common than what we don’t.”

Juvon McClenton, former AVP participant

That togetherness extends to those who run AVP, like Sue Torrey, who first attended AVP 30 years ago with her daughter. Immediately, she recognized the power of the program. She vowed to continue with AVP when she retired. And she did. Today, she is the AVP Coordinator for CMC.

In her 12 years with the program, she has gone through workshops at juvenile hall, the Men and Womens’ Honor Farm and her personal favorite because of its meaning to the participants – prison.

According to Torrey, AVP traces back to the Attica Riots of 1971 where tensions over harsh conditions in a New York prison boiled to the surface. One thousand prisoners revolted, held dozens of guards hostage and seized control. After this, a handful of those prisoners entered a Quaker meeting asking for help to decrease violence. The Quakers brought in peace activists. The three entities – the prisoners, the Quakers and the peace activists – came together and therein AVP was born.

Today, there are 33 California prisons offering AVP workshops.

Quakers, also known as members of The Society of Friends, have Christian roots and as a BBC article said, “believe that there is something of God in everybody and that each human being is of unique worth. This is why Quakers value all people equally, and oppose anything that may harm or threaten them.”

According to its website, AVP builds upon this Quaker spiritual base of respect and caring for others, but draws participants from all walks of life.

“Most of our time spent meeting and talking to other people [in AVP] is not spent in deeply authentic sharing of who you are – it leads to that,” Torrey said. “So it almost feels kind of like sacred space, not [necessarily] in a religious way.”

This kind of connection generally never gets made whether in prison or outside, she adds. “It just doesn’t happen.”

When Torrey was hired for the position, an AVP volunteer told her, “We’re not here to judge them. They’ve already been judged. We’re here to house them and treat them with respect.” And she has lived by that in her years of service.

In AVP, this respect and care for one another is universal — it’s felt by participants and volunteers alike, according to Lompoc Federal Prison AVP facilitator Stephen Pope.

Pope was involved with AVP for a while as a volunteer himself. But after enduring a difficult divorce, one of his trusted friends from AVP advised that he try the program out as a participant, not a volunteer — he did just that and he realized how truly effective the workshops were.

“It just totally stuck,” he said.

Pope isn’t the only one who speaks to the effectiveness of AVP. Testimonials of those that have volunteered with, gone through or even have experience in both capacities for AVP continue to endorse the effectiveness of the program.

One study at a Minnesota prison found that there was about a 25% reduction in anger tendencies among those that went through the 20-hour basic workshop; other studies have found similar results.

AVP starts taking effect when participants assume a new, chosen identity through an “adjective name,” Pope said.

Participants are asked to take their first name — not a nickname or gang name — and think of a positive adjective that starts with the same first letter. The adjective should represent a way that they already or want to identify with, Pope said. This practice alone has proven to make a significant impact.

“I’ve heard of examples on the yard where somebody gets you know, it looks like a fight is starting,” he said. “And somebody else will look over and say, ‘No, no, no, Daring Donny does not want to do that.’”

Pope said some participants look forward to when they can become facilitators themselves or later thank him for the opportunity to forge a new path.

Not only does AVP give them a potentially newfound purpose, but also acts as an effective tool to break the stigma around incarceration, according to Pope.

“People think of prisoners as being these nasty, huge linebacker types and a lot of them are just [normal] looking guys…” he said. “A lot of them look like some of you say, ‘Oh, that looks like my old neighbor. I have a cousin who looks like that.’”

Stephen Pope, Lompoc Federal Prison AVP facilitator

AVP isn’t the only program recognized for its human-centered approach.

Restorative Partners, for example, is a program that has similar values and practices restorative justice. According to their website, the program centers the individuals and relationships that are victims of crime and recognizes perpetrators’ obligation of accountability.

While similar, AVP has other attractive qualities of its own. Nancy Vimla has been involved with AVP since 2008. She said one of the highlights of the program is that, “You’re doing it together.”

“Each person gets to share what they experienced and listening to [others] because sometimes you’re not sure what you were, you know how you experienced it,” she said. “Yeah, including others. It’s a very magical thing.”

Pope agreed that part of what makes AVP special is the fact that there’s “almost no written material ever.” And unlike some other programs, there is also an emphasis on equality between facilitator and participant — everyone in the room is there to help one another.

“We want to do those exercises with you. And compared to many other programs, [they’re] mostly all just for the outside people to come in and say the purpose of this workshop,” he said. “The only difference is I’m not wearing a blue suit. And, you know, I know what’s on the agenda, I know the exercises. But I do that with you. I don’t preach at you about stuff.”

Pope also said AVP is a “recipe.”

The first part is “church,” he said, where participants are told to find an inner connection to something bigger than themselves. The next part is school, where they learn “concrete communication skills or meditation skills.” Then, it’s part recess — there is a balance of deep introspection and lighthearted games or activities like jumping around of Simon Says. The last part is therapy, Pope said.

Even with its reputation and global influence, AVP has dealt with some staffing and resource shortages, Pope said. It can especially be difficult to work around the lives of all AVP-associated volunteers, whether this be someone in reentry programs, chaplain’s assistants or school assistants.

“Those three groups of people have different ways of working, different motivations, different days of the week, they want, you know, right now,” he said. “And in Lompoc [we] are having a problem because since we opened up from Covid, we’re working out under the chapter and of course, all of his rooms are real busy on the weekends.”

Additionally, protocol may vary from to prison, which can make it more difficult for AVP facilitators to host workshops. Despite this, though, AVP continues to be a globally influential program.

And as an experience so intertwined with emotion and growth, AVP continues to leave its print on participants and volunteers alike. The program captures the nuance of difference while facilitating connection.

McClenton, for example, is just one person whose life has been permanently changed for the better thanks to AVP.

“I’m sorry for the harm I caused but I’m not sorry for the suffering I experienced because it propelled me to do the work, to connect with other humans, to be of service,” he said.

Additional reporting done by Cole Pressler.