This story was originally published in the Mustang News March print issue.

When she first started teaching an Intro to Microbiology course, Cal Poly biology professor Dr. Alejandra Yep noticed there were a lot of inaccurate preconceived ideas about the subject among her students. She realized there is no microbiology in the science traditionally taught in K-12 education.

“People come already thinking things about microbes that are completely wrong, but they don’t even realize it,” Yep said. “This is really dangerous. The anti-vaccination movements are growing. People should know more.”

Yep decided to mitigate this knowledge gap. She went to her sons’ elementary school to teach a mini-lesson on microbiology. Students tested for germs before and after washing their hands with swabs and petri dishes.

Yep’s children went to Pacheco Elementary School – a school with a bilingual education program two miles from Cal Poly. Instruction in this program begins in 90% Spanish during kindergarten and progresses to 50% Spanish and 50% English by fourth grade.

Almost instinctively, Yep taught the lesson in Spanish – Spanish is her first language and the language she speaks to her kids. Just as her students learned from her, Yep gained new insight from them.

“One of the kids told me, ‘That was so much fun. I didn’t know that Spanish-speaking moms could be scientists.’” Yep said. “That’s the thing I couldn’t forget.”

With the “perfect partner” Jasmine Nation, Yep’s experience inspired the creation of Nuestra Ciencia in the spring of 2021, a club to bring more Cal Poly students to schools to teach science in Spanish. Nation, a liberal studies professor who learned Spanish in college, teaches courses for future STEM educators.

Even though these bilingual elementary schools are designed to educate students in Spanish, science is not usually included as a lesson in Spanish, according to Nation.

“This is a unique experience that we’re providing for them to see that science doesn’t have any language,” Nation said. “You are a scientist just by being curious about how the world works.”

Yep believes Cal Poly students have a celebrity effect on the younger students. Every time a younger student is taught a lesson by a Cal Poly student, she says they get excited about and engaged in the lesson.

Biomedical engineering junior and native Spanish-speaker Natali Ceja started teaching as part of a BEACoN research role and later Nuestra Ciencia. While working with the students, she found that it was often simple to form relationships with the students.

“When we would say, ‘Oh, we’re from this part of Mexico’, a lot of them would be like, ‘Oh, that’s where my parents are from,’” Ceja said. “Automatically, you’ll get that little connection. So when you work with them in groups, they’ll want to talk to you and try to get to know you.”

Ceja added that even the students who struggle working in a classroom setting are usually engaged with Cal Poly students due to the connections Spanish-speaking creates.

After a few years of visiting schools with a small group of students as a club Yep and Nation started a Spanish section of “SCM 302: The Learn By Doing Lab Teaching Practicum” during winter 2023 – a class designed to teach students how to teach science.

SCM 302: The Learn By Doing Teaching Practicum

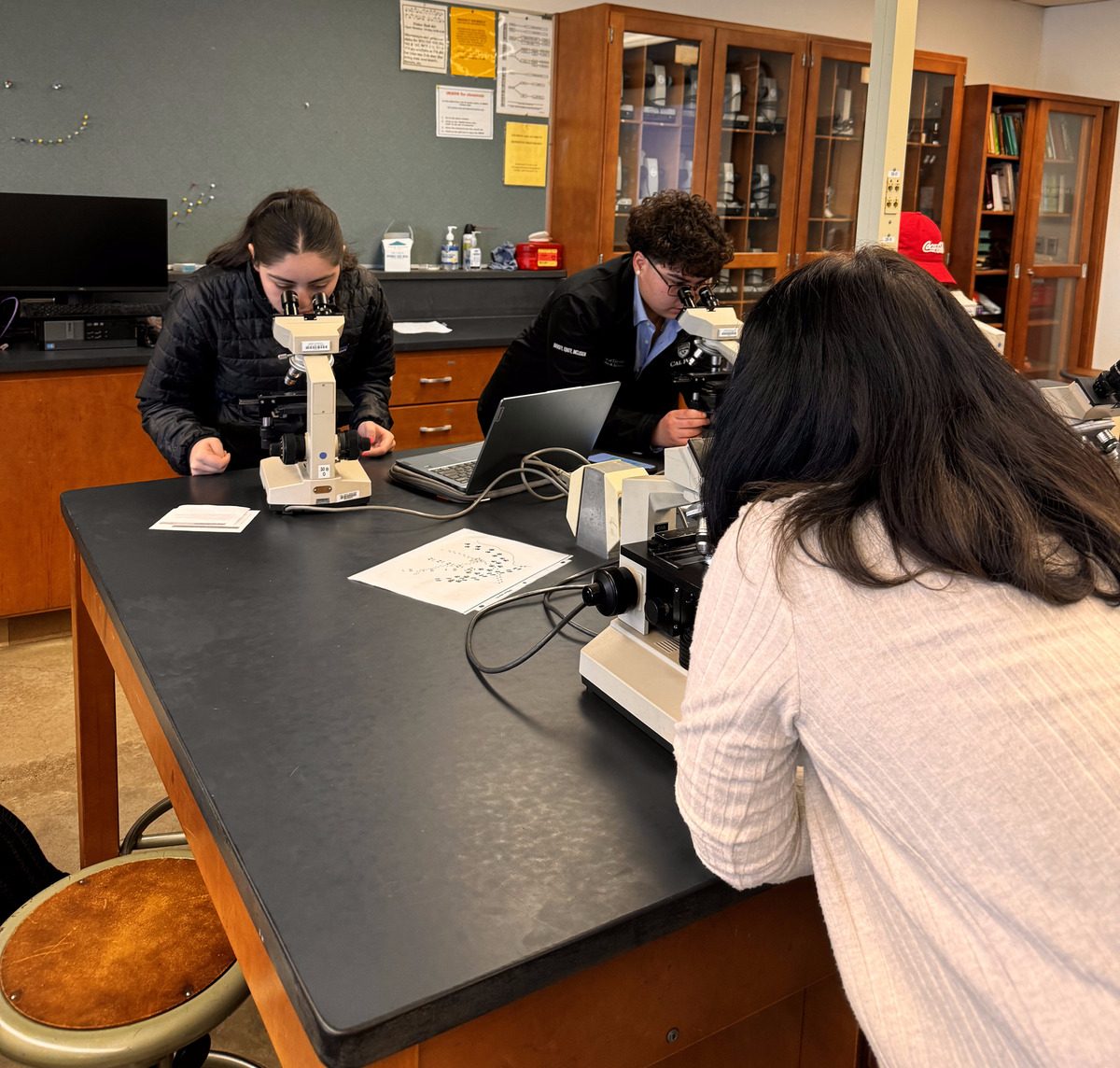

In Building 53, Yep and Nation teach a class that looks like many other classes at Cal Poly. Students sit in groups clacking away on laptops – some are seated in front of microscopes and others sit around a collection of moldy petri dishes.

This section of The Learn By Doing Lab Teaching Practicum (SCM 302) is unique not because of how it looks, but because of how it sounds. Spanish is used in Yep and Nation’s lectures, class presentations and non-academic conversations between students.

“I think it’s the first class at [Cal Poly] that is run in Spanish, but the subject is not Spanish,” Yep said. “We’re not teaching the Spanish language here. The students need to be proficient enough to be able to communicate verbally in Spanish.”

These Cal Poly students learned Spanish in a variety of ways, at home, in school or while abroad. The course spends the first few weeks preparing lessons to be taught in Spanish to students from schools with a bilingual program, like Pacheco Elementary School.

Liberal studies senior Ana Banuelos grew up speaking Spanish at home like the students in these bilingual programs. There was always a barrier when she would get home after school and try to talk about what she learned that day.

“I never told my parents what I did at school because I didn’t want to translate,” Banuelos said. “It felt like so much. The idea that these kids will be going home to their parents that speak Spanish with something to talk about is pretty cool.”

There is often a disconnect between native Spanish-speaking students and their families when they learn at an English-taught school. This program helps some undergraduate students talk about academics with their parents for the first time, according to Nation.

“Students have said, ‘This is the first class that my mom was really invested in and wanted to hear more about,’” Nation said. “Or ‘I would ask for help with translation and my mom was like, see, your Spanish is important.’ This is the way they would have liked to learn science. It’s really empowering for [them] to be a role model and teach other kids in the way that [they] would have wanted to.”

Beyond inspiring young Spanish speakers, this project shows the native Spanish-speaking undergraduates involved in it a new reality: academics in Spanish. Teaching in Spanish helps students build a bridge between the Spanish speaking self they use around their family or friends and the English speaking self they use in school, according to Yep.

“Spanish is a language that is not just to talk about foods and family things,” Yep said. “It’s a full fledged language that can be used for anything. [This program] helps many students with this dissociation between the academic person they make speaking English and the family or friends self speaking Spanish.”

Yep also thinks this program has helped reconnect to Spanish in ways she has not been able to for years.

“It’s a good feeling to be teaching science in Spanish because when I left Argentina I also stopped using Spanish for science,” Yep said. “Microbiology can be in Spanish. I haven’t done that since I was an undergrad. I use it to talk to my kids or to my friends, but not for academics.”

Serving Hispanic students as an institution

Nuestra Ciencia and the Spanish section of SCM 302 are among the spaces for Spanish-speaking students at Cal Poly as the University moves towards becoming federally designated as a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI).

As of 2022, Cal Poly’s Latinx enrollment was 21.1% of total undergraduate students, according to the HSI executive summary report, and 24% of the latest class of admitted students identified as Latinx according to the Office of University Diversity and Inclusion (OUDI).

“The classification as an HSI, sadly, is based on a percentage of enrollment,” Yep said. “There’s nothing built into the definition of becoming an HSI that says that you actually have to serve them.”

The only requirement to be granted HSI designation is for eligible universities to have enrollment of undergraduate full-time students that are at least 25% Hispanic, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

“Here at Cal Poly, I think the people involved in this process are very cognizant of this and that we’re going to actually become a Hispanic Serving Institution, emphasis on the serving part,” Yep said.

Yep was born and raised in Argentina. Her family spoke Spanish, her community spoke Spanish and, most notably, her educators spoke Spanish. When she first came to San Luis Obispo, she did not realize the significance of being a Spanish-speaking academic.

Liberal studies senior April Valdez Garcia found it hard to get involved at Cal Poly as a transfer student. After her classes, she would immediately go back to her home in Santa Maria, until a friend convinced her to join Nuestra Ciencia and SCM 302.

“My Spanish isn’t the best,” Valdez Garcia said. “It’s a community where I can come in and they don’t judge me on my Spanish. I really enjoy coming to Cal Poly now because it’s a community for people that speak Spanish in any way. The experience of teaching Spanish is giving me a lot of confidence.”

Students like Valdez Garcia involved in Nuestra Ciencia have felt supported in this space and a part of a community.

“We’ve heard over and over again, ‘This is the first time I felt like I belonged at Cal Poly,’” Nation said. “[They say,] ‘This is something where I feel like I’m making a difference. I’m giving back to my community. I’m part of a research group. I’m part of a teaching group.’ I think more programs that help students to feel like they’re contributing are needed.”

This quarter is the second quarter that a Spanish section of SCM 302 was offered. After the first section of the course, Yep and Nation received “super emotional” and “impactful” feedback.

“They were sharing all these personal things about what it meant to be teaching in this language,” Nation said. “One of our facilitators said, ‘I never had this experience and I would have benefited so much as a child. It was so great for me to be able to do this because I felt like I was healing my inner child.’”

Throughout her career, Nation has studied and researched science education. She has found that a lot of students, specifically women, students of color and students of different ability, are pushed out of science. They often think it is because they simply are not scientists, but Nation disagrees.

“A lot of students will come in scared of science or they’ll say, ‘I’ve never liked a science class,’” Nation said. “That’s because the class wasn’t taught the right way. Not because you’re not a scientist. Kids are natural scientists.”

Yep never wants a language barrier to stop a child from thinking they could become a scientist. She also never wants them to think they cannot pursue a higher degree because they speak Spanish at home.

“Families said, ‘Well college is not for us,’” Yep said. “But why? Why is it not for you? If it’s not for you because you prefer to do another thing, then okay. But if you think it’s not an option for you, then I have issues. It should be an option that you don’t need to choose, but it has to be a viable option.”

Nation and Yep hope to use this program to teach future educators how to create inclusive science instruction to make all students love science, even the students whose first language is not English.